The world is set to pay a hefty price for Russia’s war against Ukraine. A humanitarian crisis is unfolding before our eyes, leaving thousands dead, forcing millions of refugees to flee their homes and threatening an economic recovery that was underway after two years of the pandemic. As Russia and Ukraine are large commodity exporters, the war has sent energy and food prices soaring, making life much harder for many people across the world.

The extent to which growth will be lower and inflation higher will depend on how the war evolves, but it is clear the poorest will be hit hardest. The price of this war is high and will need to be shared.

The global economy is set to weaken sharply in our projections. We estimate world growth to be 3% in 2022 – down from the 4½ per cent we projected last December – and 2¾ per cent in 2023. Inflation projections now stand at nearly 9% in OECD countries in 2022, twice what we were previously projecting. Elevated inflation across the globe is eroding households’ real disposable income and living standards, and in turn lowering consumption. Uncertainty is deterring business investment and threatening to curb supply for years to come. At the same time, China’s zero-Covid policy continues to weigh on the global outlook, lowering domestic growth and disrupting global supply chains.

With risks biased to the downside, the price of war could be even higher. The conflict is disrupting the distribution of basic food and energy, fuelling higher inflation everywhere and threatening low-income countries in particular. European economies are struggling to wean themselves off Russian fuel. but because alternative energy sources may not be easy to ramp up quickly, there is a risk of higher prices or even shortages. If the war escalates or becomes more protracted, the outlook would worsen, particularly for low-income countries and Europe.

Limiting Russia’s ability to finance the war, as is intended by an embargo on Russian oil exports, is essential for speeding up an end to this devastating conflict.

Meanwhile, we must minimise the humanitarian, economic and social consequences.

The first urgency is to avoid a food crisis. Today, the world is producing enough cereals to feed everyone, but prices are very high and the risk is that this production will not reach those who need it most. Global cooperation is needed to ensure that food reaches consumers at affordable prices, in particular in low-income and emerging-market economies. This may require more international aid as well as cooperation in the logistics of shipping and distributing to countries in need. The flaws of global vaccine distribution are still fresh in our memory. Let’s not repeat them.

Second, inflation has strong distributional effects. It will help drive down debt, including public debt, but it is also eroding real income, savings and purchasing power. At the same time, it may affect firms’ profits and capacity to invest and create jobs. Inflation is a burden, which must be shared fairly among people and firms, between profit and wages. Governments also have to play a role through support targeted to those most vulnerable to rising food and energy inflation.

Next, monetary and fiscal policy need to adjust to these extraordinary circumstances.

Globally, the elevated levels of inflation and employment today suggest there is no longer a need for monetary policy accommodation. However, in many regions inflation is driven by food and energy. If monetary policy cannot address such supply shocks, it can send signals that it will not allow inflation to rise or spread further. Removing accommodation is therefore warranted across the globe, but with particular caution in Europe where supply-driven inflation dominates. Conversely, wherever inflation is driven by over-buoyant demand, as in the United States, monetary policy can tighten faster to reduce such excess.

Fiscal policy management is particularly complex. Because of the current levels of growth, employment and inflation, the need for economy-wide income support has disappeared and should be replaced by better targeted measures. The war in Ukraine has raised the need for higher public investment in defence and for greater urgency in the transition to greener energy. This comes on top of other investment needs like health, digitalisation, ageing and education, and as public debts remain high. This conundrum can only be resolved with a stronger focus on prioritisation from governments. In Europe, the integration of the region and high exposure to the war calls for more solidarity in defence and energy spending.

The war has exposed how energy security and climate mitigation are intertwined. Governments need to shift gear to accelerate the energy transition. The emergency response to a possible energy crisis has turned out to be a stark scramble for alternative sources of fossil fuels and to increase coal use. This can only be temporary as it is the opposite of what the world needs, which is a rapid increase in investment in, and consumption of, cleaner energy. But clean energy requires inputs, minerals and intermediate materials which come from all over the planet. Put simply, the cleaner the energy, the larger and the more geographically diverse the value chains will have to be. There will be no climate mitigation without open trade and resilient global value chains.

The world is already paying the price for Russia’s aggression. The choices made by policymakers and citizens will be crucial to determining how that price will be distributed across people and countries.

8 June 2022

Laurence Boone

OECD Chief Economist and Deputy Secretary-General

Colombia

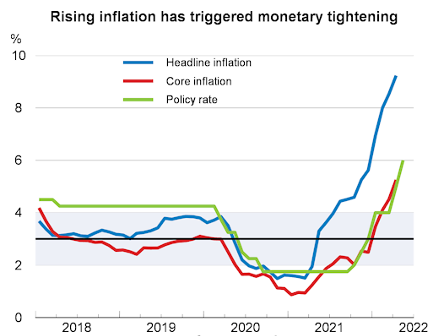

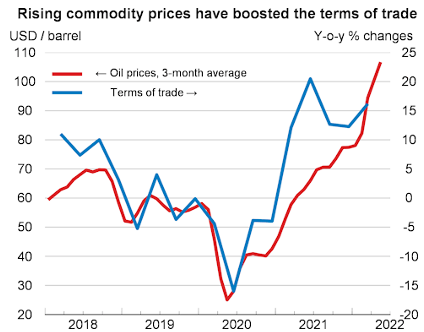

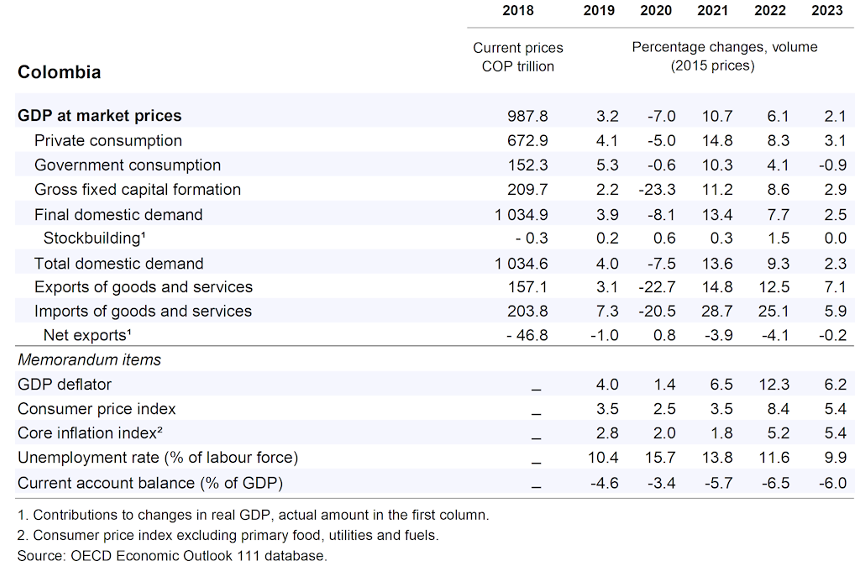

GDP is projected to grow by 6.1% in 2022 and 2.1% in 2023. Private consumption is the main driver of the recovery, driven by a gradual pick-up of employment. Strong commodity prices have improved the terms of trade and are supporting fiscal outcomes, against the background of rising external demand. Inflation has risen well above target, initially driven by food and energy prices, which have particularly affected low-income households. More recently, however, inflationary pressures have become increasingly widespread.

Monetary policy tightening has accelerated substantially and financial conditions are expected to remain tight until end-2023. Fiscal policy will provide continuous support to vulnerable households during 2022, while spending reductions in other areas will usher in a gradual fiscal adjustment that is set to intensify in 2023. A recent fiscal reform has laid the grounds for this adjustment, but stabilising public debt will require additional efforts. Addressing long-standing challenges like low tax revenues, low tax progressivity and low coverage of social benefits could ensure a more inclusive recovery.

Rising commodity prices are supporting exports and public revenues

A strong rebound of activity during the second half of 2021 brought GDP almost back to the levels projected prior to the pandemic. In early 2022, the recovery slowed amid a sharp decline in consumer confidence, although unemployment continues to fall while employment remains on a rising trend. Rising female employment has narrowed the gender employment gap. Annual inflation has reached 9.2% and is weighing on consumer spending, especially for low-income households, as food prices have risen by 26% year-on-year. Recent negotiations have resulted in a 10% increase of the minimum wage, while wage growth in manufacturing and retail sectors have been strong. While Colombia has only a small direct trade and financial exposure to Russia and Ukraine, it is a major commodity exporter and higher oil and mineral prices have buttressed exports and fiscal outcomes.

Colombia: Inflation indicators

Source: DANE; BRC; Refinitiv; and OECD Economic Outlook 111 database.

StatLink https://stat.link/fbeh9q

Colombia: Demand, output and prices

StatLink https://stat.link/zr0p14

Monetary and fiscal policies are tightening over 2022 and 2023

The monetary policy rate has risen by 425 basis points since 2021, and tightening has accelerated this year. Broad-based inflationary pressures will likely require maintaining this accelerated pace to restrictive levels of 8%, and then keeping interest rates stable until late 2023. Fiscal policy has moved from unprecedented support to a gradual consolidation as the recovery gained pace. Exceptional income support to vulnerable households will be maintained until the end of 2022, while other spending areas are set for a significant consolidation, including public investment and general public services expenditures. Fiscal consolidation is meant to accelerate in 2023, if the incoming administration honours current fiscal plans. Improving fiscal outcomes will shore up confidence, after gross public debt has risen to 62% of GDP in 2021, up from 50% in 2019.

Despite a slowdown, growth will nonetheless remain solid

Moderate growth will resume in 2022, with a slight acceleration through 2023. Private consumption will gather steam in 2023 as high inflation abates and unemployment recedes. Investment will be driven by a strong construction sector attenuated by tighter financial conditions. Primary exports from oil and mining will benefit from high global prices, at least temporarily, which will also support investment in these sectors. Potential risks surround the adherence to fiscal plans, given that a significant part of the planned fiscal adjustment will have to be implemented by the next administration. Sudden sentiment changes in global financial markets, possibly related to changes in global interest rates, could increase financing costs and affect portfolio capital flows. These have been volatile in the recent past, although the impact has been cushioned by sizeable reserves and continuous access to multilateral financing.

Ambitious reform could address structural bottlenecks and improve equity

The pandemic has exacerbated previous challenges in poverty, inequality and labour market informality, while interrupting many children’s education for up to 18 months. Healing these scars will require additional spending on social protection, health and education. This requires mobilising additional public revenues, as does maintaining adequate levels of public investment. It also provides an opportunity for a progressive reform of the tax system and its widespread exemptions and special rates, most of which favour the better off. Replacing social security charges on formal-sector wages with general tax revenues would reduce high non-wage labour costs and curb labour informality, which currently affects 60% of the workforce. A significant overhaul of the fragmented pension system could increase its currently narrow coverage and reduce old-age poverty, while fragmented cash benefit programmes could be merged into a universal social safety net, building on recent advances in social registries. Steps to reduce trade barriers and strengthen competition could facilitate necessary reallocation processes and bolster productivity. A majority of electricity is already generated from renewable, mostly hydroelectric, sources, ensuring energy security, but there is scope to expand the use of wind and solar energy to reduce the reliance on fossil fuels. Defining a timeline for raising and expanding the carbon tax could support these efforts.